I wrote this up a whle ago when trying to explain decentralized identity concepts to newcomers, which included people who would have to soon communicate these concepts to other people. So a large focus was visuals, analogies, etc, as well as common misconceptions. Unfortunately I lost some beautiful formatting in the doc => markdown conversion, but I’ll try to recover that later, especially if this content is useful.

Foundational Concepts

Terms and Definitions

These are my working definitions of core terms, designed to balance correctness and simplicity, not pedantry.

| Term | Definition |

| Decentralized Identity | Set of technical standards and principles seeking to enable a shift toward more individual control over digital identities and personal data

|

| Verifiable Credential (VC) | Tamper-evident claim made by an issuer about a subject (entity, often a person) whose authorship can be cryptographically verified

|

| Decentralized Identifier (DID) | An identifier (or label) that enables cryptographically verifiable digital identity. In contrast to typical digital identifiers, DIDs have been designed so that they may be decoupled from centralized authorities or identity providers, and can be entirely under the control of an individual, without needing permission from a third party

More about it:

|

Analogies

Here are (what I hope are) useful analogies for newcomers, or anyone who doesn’t care to get into the technical details. I’ve gone the extra mile and compared/contrasted the analogized entities, thereby beating the analogies into the ground, but hopefully this is helpful for your own mental model.

Verifiable Credentials and Envelopes

Figure 1: Postal envelope for mailing a letter.

Photo credit Anne Nygård | Unsplash

Figure 1: Postal envelope for mailing a letter.

Photo credit Anne Nygård | Unsplash

A Verifiable Credential is like an envelope (used to mail a letter):

- It’s a lightweight wrapper around any content

- It provides functional similarities:

- “Content integrity”:

- There is an assumption / convention is that the envelope contents don’t get tampered with

- But to be more precise, if the physical envelope was tampered with, you would be able to detect it. In VCs (and digital signatures) we call this tamper-evidence

- In VCs this is achieved through the VC proof – if the contents are modified, the cryptographic signature (or other proof mechanism) wouldn’t match.

- “Authenticity”:

- Looking at the envelope, you know who it’s from, who it’s going to

- In VCs, this is enabled through VC issuer and credentialSubject properties

- “Content integrity”:

- We’ve all steamed open envelopes as a child and therefore know the failure modes. Graphically, you might use a Game of Thrones-looking envelope with a wax seal / sigil (see Figure 2) to make it look really secure but …

- The analogy breaks down pretty quickly, because:

- In contrast to physical envelopes, VCs are secured by cryptography – not the act of licking

- A physical envelope hides its contents (letter), but a VC is not hidden or even necessarily encrypted. VCs provide digital signatures, which is the “content integrity” part described above.

Figure 2: Envelope with a wax seal. Photo credit Svetlozar Hristov | iStock

Figure 2: Envelope with a wax seal. Photo credit Svetlozar Hristov | iStock

Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) and…

DIDs and Web URLs

DIDs are strings that look like this:

did:example:1234

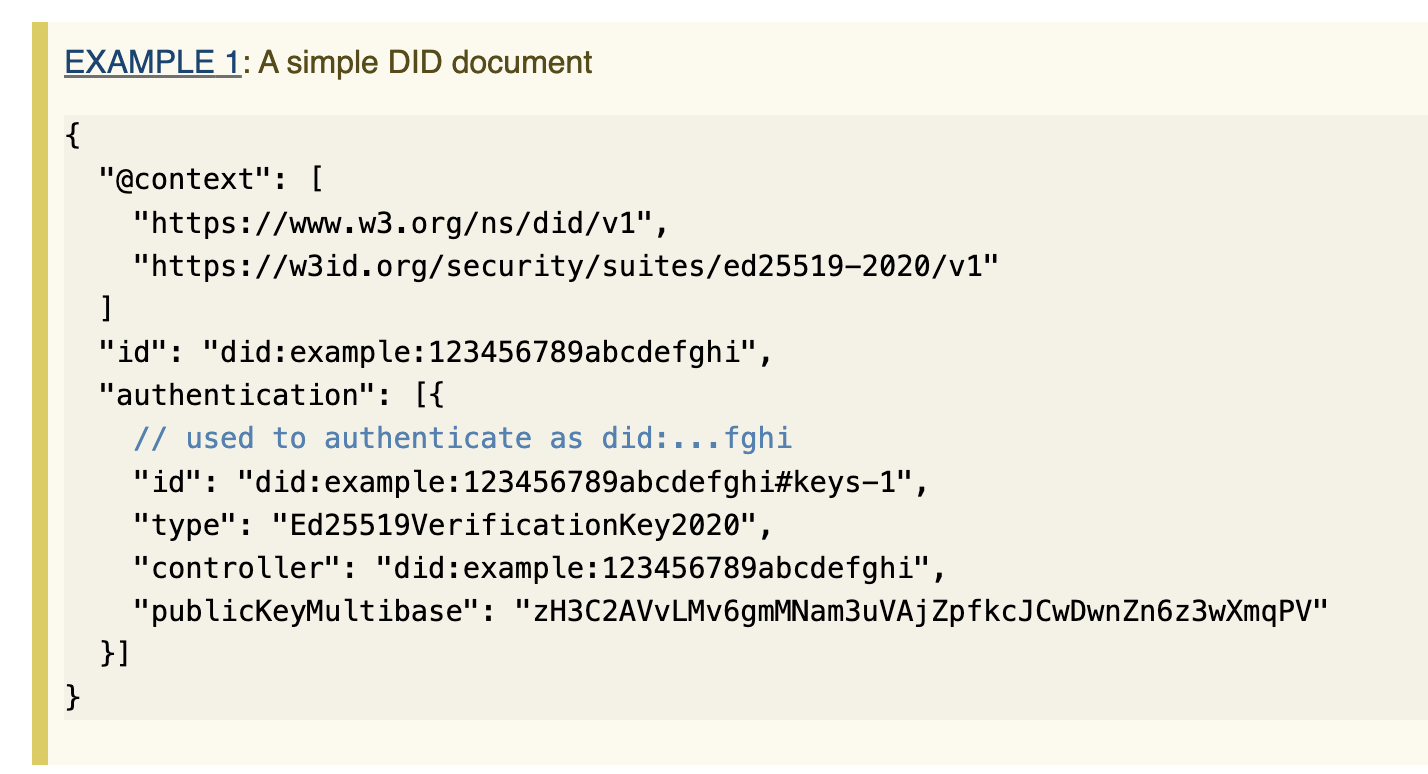

Notice that it looks like a web URL, and actually they are related. Both are types of URIs (Uniform Resource Identifiers). Just as a web browser can take a web URL and render a web page, software that understands a DID can retrieve its associated “DID Document”.

Or visually, just as https://twitter.com/ resolves to a twitter web page:

did:example:1234 resolves to a DID document:

DIDs vs Social Security Numbers (SSNs)

- This analogy tends to be helpful as a contrast, or punching bag, because in the US we know how SSNs can easily be compromised and used for identity theft

- Specifically, it’s shockingly easy for someone to learn your SSN plus a few other tidbits about you, and start hijacking your identity. So instead, we say “imagine it’s a SSN but you (and only you) can use it because you can prove it’s yours”

- The DID/SSN contrast is further helpful when talking to the relative advantages of DIDs because:

- SSNs are used in a loose way; attributes are associated with them whether the person associated with the SSN is involved or not.

- In contrast, DIDs are expected to be used in protocols where proof of control is required, so a loose claim assigned to a DID is less valuable to a RP

- Some other notable distinctions:

- Whereas you have 1 SSN, people are expected to have lots of DIDs for different purposes. Wallets/software help people manage them

- In contrast to SSNs, people should never be expected to remember their DIDs

- SSNs are a government-issued identifier whereas DIDs may be self-issued/created. DIDs could be bestowed upon you, but even in this case you’d likely (because they’re not very interesting otherwise) be able to tie them to you through authentication or some means.

- Note that DIDs are being considered as a data type for some national digital ID systems

- Whereas an SSN is a flat string, but a DID “resolves” to a DID document which contains data like public keys, services, etc, as shown in Figure 3

DIDs vs Cryptographic Keys (or addresses, like a cryptocurrency address)

One oversimplified shorthand is to think of DIDs as cryptographic keys with built in lifecycle, like you can rotate keys. Because the DID string resolves to a DID document, you can update the document over time.

Pitfalls and Misconceptions

Myths and Facts

| Myth or Misconception | Fact |

| Correctness of VCs | |

| A VC must be logically true or factually correct | A VC simply contains assertions (statements) made by an issuer. An issuer can assert a claim that is subjective, flawed, or demonstrably false. And certainly, the claim within a VC is not intended to be provably correct based on formal logical methods.

The issuer of a VC can be anyone and they can say whatever they want. It’s up to verifiers or relying parties to decide whom and what they trust. Example: In 2016 we briefly discussed using VCs to help address discovery of reliable sources of news information and, while it could offer some benefits here and there, without massive effort it would likely just reinforce existing echo chambers |

| Where personal data lives | |

| Personal data is on-chain | Early decentralized id solutions did put personal data (or hashes of it) on-chain but most have moved away from this architecture.

As of the last couple of years, on-chain items are typically restricted to, at most:

|

| But what if it’s encrypted? | |

| If the data is encrypted, it’s ok to put it on-chain | No, we want to avoid this too. As you probably know, the encryption algorithms you use over time have changed for a combination of reasons including stronger processing power and exploits found.

We also worry about the impact of quantum computing, enabling at some point, all of this to be effectively clear text on a blockchain. Stop trying to put unnecessary data on a blockchain. It’s a super wasteful way to store data anyway. |

| Privacy, correlation, and hashes of personal data | |

| Hashing credentials (or performing some similar 1-way function) containing personal data before putting it on chain makes it ok | Even the result of 1-way functions, when combined with the permanence of blockchains, may result in privacy concerns – particularly, the ability for other parties to perform correlation. In fact, frameworks like GDPR also call out concerns around correlatable data, including that generated by hashed data.

The specific threats can take a while to describe (a topic for later), but in general, you want to make it hard for an attacker (or lurker) to learn additional information about a person over time through repeated use of digital fingerprints traceable to the same entity. This is similar to how reuse of crypto addresses enables correlating one’s behavior, and sometimes doxxing, over time. Chainalysis and similar tools make it easy to discover a large amount of additional user information based on address reuse, flow, and transaction history. Now imagine if you add identity data into the mix – a la Celsius. |

| Use of DIDs in VCs | |

| VCs require use of DIDs | VCs identify issuers and subjects with URIs, so it can be a web site, etc.

It can also be a DID, but it doesn’t have to be. |

| Number of DIDs | |

| A person will have 1 DID | A person will likely have many DIDs, and ideally most of these are under their control (self-custodied, meaning they own corresponding private keys or proof)

Exact patterns are still emerging:

|

| "Credential" vs security credential | |

| "Credential" refers to security access credentials, like login usernames and passwords, etc | In the context of "Verifiable Credential" it means what we've discussed above. [More details are here](https://www.okimsrazor.com/verifiable_credentials/). Just stating this for your awareness; this perception is commonly for people working in identity and access management. |

| What is a credential "subject" | |

| "Subject" refers to a topic, school subject, etc | In the context of verifiable credentials it’s the entity (commonly a human) that the claim/statement is made about. |

| Who can issue VCs | |

| Only traditional "authorities" (educational institutions, governments, etc) can issue VCs | Anyone can issue a VC, ranging from traditional authorities to, well, you, your friends, peers, etc. Non-person entities can issue them as well.

As covered previously, this doesn’t mean relying parties have to accept a VC issued by your brother claiming that you can drive. It’s up to relying parties or verifiers to decide whom to trust. They may accomplish this through trust registries or other signals of reputation. |

Other uncomfortable conversations

| In brief | Long story |

| "Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI)" vs "Decentralized Identity" | |

| These are kind of synonyms but be aware that, depending on who you’re talking to, SSI may be off-putting |

|

| "Verified Credentials": note verified not verifiable | |

| This is a generally acceptable synonym and you should give the benefit of the doubt.

It could be a good talking point, making this an uncomfortable conversation not for you, but probably for your interlocutor who really doesn’t care. |

In contrast to traditional credentials where the exchange may be between 2 trusted parties (e.g., two financial insts communicating directly with each other via secure means), VCs are meant to be re-verified (within reason) on every use because the issuer can update the lifecycle (revoke it, etc).

Within reason means that, depending on the type of credential, there are realistic simplifications you might make about credential update frequency. E.g., the OFAC SDN list is only updated / published 1x day so in a case where you know that’s the only factor influencing the validity, you wouldn’t need to recheck every minute (just for example) That means a VC is not in a permanently verified state, but it should be verified when used. It is verifiable, not verified. |